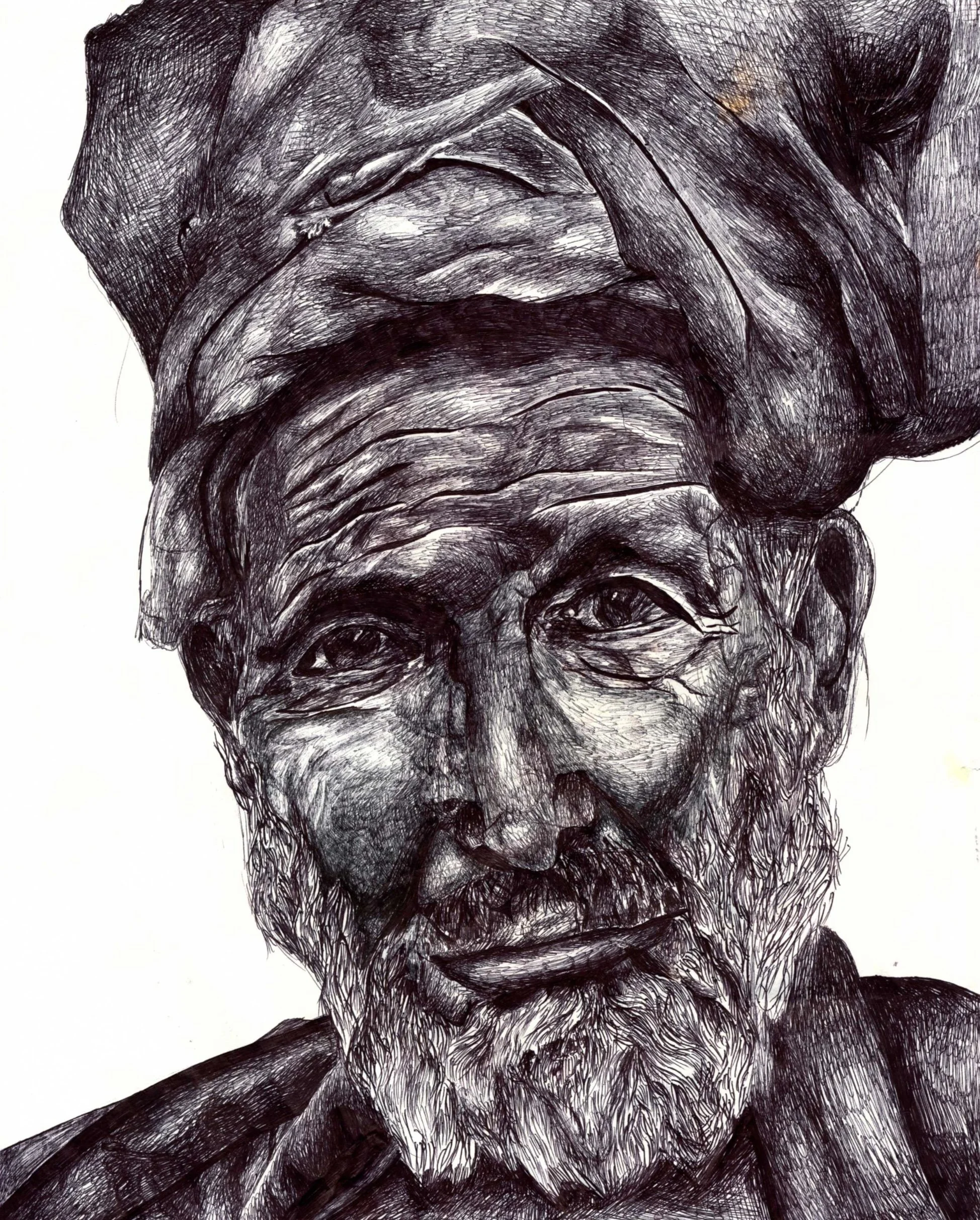

Every Village Has its Madman

by Angeliki Cintrón

Every summer devolves into ghost stories carved

out of bellies with a paring knife, told underlit

and blinded by an industrial strength flashlight.

The youngest brothers saw dancing ladies in white,

bolted home. The older brother heard a beldam,

her cackle blown through the mangled branches

of an old Daphne. The cousin exposed a shadow

man’s hiding spot in a game of cops and robbers.

Every summer the stories whirlpool until they snag

onto Faráo, who was spotted gorging himself

on figs two days after his burial. He had walked

into the Aegean, suitcase in hand, pulled down

by visions of a boat carrying him to the port town.

After the war, but before the tunnel exploded

out of the mountains and connected the village

to automobile traffic, electricity, and cousins,

the villagers trapped Faráo in the dry soil of a story.

Every summer the kids return, relive the day

the taverna owner pulled a paring knife out

of his apron, spilled open the bloat of fresh figs

swelling Faráo’s stomach, exhaled the vapor

of decaying sugar. Every summer the kids retell

the ghost stories as their grandparents’ eyes,

crow’s feet begin to superimpose onto their faces.

Every summer the flashlight passes. The stories,

the sober curiosity remain. Faráo swells up with figs

and salt water. He never makes it to the port town.

He always ends up sliced, opened, observed.